Quadrille: A four part poem

I

A day to remember

An era of harmony

A melody lost somewhere

In the wind

A last gasp, a sigh

A whisper of yesterday

The ghost given up

The cards surrendered…

“Aye, ante up, m’boys

If ye’ve money to play”

“OK,” says I

“Deal me in”

******************************

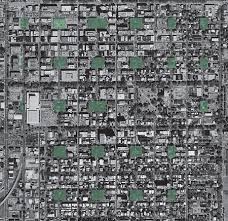

II A grid

A giant grid: a way to map, to measure, to see the world. But never exactly, my dear. Never exactly. Science and Mathematics have refined our ability to measure and define our universe, but a certain level of uncertainty (Prof. Planck’s) always remains. The world can not be explained perfectly, only nearly perfectly. It’s a question of how close we can get it.

A giant grid: a way to map, to measure, to see the world. But never exactly, my dear. Never exactly. Science and Mathematics have refined our ability to measure and define our universe, but a certain level of uncertainty (Prof. Planck’s) always remains. The world can not be explained perfectly, only nearly perfectly. It’s a question of how close we can get it.

An uncertainty of measurement always exists. The great laws of physics never apply exactly. Plane geometry is inadequate to relativistic space; non-Euclidian geometry is necessary. We only make better and better approximations.

However, these approximations, these models, are nonetheless very useful. When we imagine that a line is perfectly straight, well, even though it isn’t really perfectly straight, we can make believe it’s perfectly straight and we can build pyramids and obelisks, and recently, a lot of shopping centers.

*******************************************

III

When did humans first build things square?

When did humans first build things square?

When did one of our ancestors look out at the horizon at the end of the day and say to himself: “Hey, I see four directions out there! Let’s see, there’s north, and south and east and …”

That fellow must have had quite an epiphany (or am I just projecting?)

IV

After that north – south, east – west discovery, after maybe 20 or 30 thousand years, Rene Descartes lay sick in bed, poor fella, looking up at the ceiling. A fly walks (upside down of course) across the ceiling, and the great mathematician and philosopher in his mind superimposes rows and columns of lines onto the ceiling in order to demarcate the fly’s position- and wham, analytic geometry is invented. The heretofore separate domains of Geometry and Algebra are bridged. A hearty thanks and a hats off to Rene Descartes, who, after all, could have skipped over the analytic geometry and just said to himself: “Hey, how come a fly can walk upside down?”

After that north – south, east – west discovery, after maybe 20 or 30 thousand years, Rene Descartes lay sick in bed, poor fella, looking up at the ceiling. A fly walks (upside down of course) across the ceiling, and the great mathematician and philosopher in his mind superimposes rows and columns of lines onto the ceiling in order to demarcate the fly’s position- and wham, analytic geometry is invented. The heretofore separate domains of Geometry and Algebra are bridged. A hearty thanks and a hats off to Rene Descartes, who, after all, could have skipped over the analytic geometry and just said to himself: “Hey, how come a fly can walk upside down?”